All wars are to be deeply regretted, even when their causes are believed righteous and we seek to honour the fortitude and courage of those who fought in them. Back in the 1980s the media accounts of the Falklands War were understandably sanitised; the full story of what really happened is only just becoming more widely known, although in truth only those who have themselves gone through such harrowing experiences can fully know their physical and mental cost. So we should not find it surprising that veterans and their families often find comfort in discussing their experiences with other combatants and bereaved families, even sometimes those on the opposing side of a conflict. The shared feelings of loss, pain, and mental anguish can override partisan considerations. Combatants may have stood beneath different flags, but their suffering and distress is common ground.

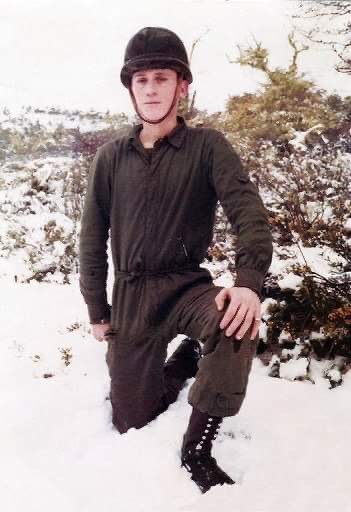

Mark Eyles-Thomas is well known to West Kent Freemasons, having been a highly esteemed Deputy Provincial Grand Master. Not everyone will be aware that he is a veteran of the Falklands Campaign. He joined the 3rd Battalion, The Parachute Regiment, in February 1982 when just seventeen years old. Less than three months later, with his comrades, he left Portsmouth bound for the South Atlantic on board the SS Canberra, a cruise liner hastily recalled from a Mediterranean cruise. Sadly, not all those who sailed with Mark that day would return home safely; to mark the 25th anniversary of the conflict Mark wrote a book about his experiences. in which he described the death in action of three close friends, who like him had enlisted as boy soldiers.

It was at a book-signing event that Mark was unexpectedly given the Argentinian soldier’s helmet, that was to inspire his remarkable quest. The helmet had been brought back as a memento by a Falklands veteran, who later gave it to Mark to display with the other memorabilia that he took to book signings and commemorative events. When such events became less frequent Mark put these items into storage, and that is where this story might have ended, but in 2021 a military enthusiast friend of Mark’s, named Mark Kirby, asked if he might examine them. On examining the helmet he pointed out that the name ‘SIRTORI’ was handwritten on its interior headband and said that if Mark ever wanted to find out more about the helmet’s owner that name could be researched in the Argentinian military records.

Knowing the family name of its owner made the helmet ‘come alive’ for Mark; he began to wonder about the soldier who had worn it in action, his background, did he survive the war, and what had later become of him? So began his quest to find out more, but Mark had no idea where it was eventually to lead him.

Mark started by getting back in touch with Mark Kirby, to ask if he could find out any more information. He checked the list of veterans of the Guerra de Malvinas (Falklands War) on the Argentinian Ministry of Defence’s website, and found only one veteran with that family name. This was Daniel Francisco Sirtori, born in 1962; his family home was at Chajari in north east Argentina, a small city known for its therapeutic hot springs.

Further investigations revealed that in the early 1980s Daniel had been called up for compulsory military service, and did his initial military training at the Parque Pereira Instruction Centre near Buenos Aires. Daniel then joined the 5th Marine Infantry Battalion based in Tierra del Fuego. In April 1982 his unit was posted to the Malvinas (Falklands Islands), where in June Daniel tool part in the hard-fought Battle at Mount Tumbledown on the outskirts of Stanley, the islands’ capital.

After the war Daniel returned home to work in a mechanics workshop and raise his family; but sadly, as for so many veterans, the trauma of his combat experiences made returning to normal life very difficult. Daniel fought long and hard against PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder), but never came to terms with the terrible burden of what he had seen and suffered in the Falklands. Those who knew him spoke of how ‘for years he fought a post-war struggle, as hard and ruthless as the Malvinas fighting’. Sadly, Daniel took his own life in June 1999, just weeks before his 37th birthday, another casualty of war; he left behind a young family who had loved and supported him throughout his struggle with PTSD.

Now more than ever Mark felt that he should reach out to the Sirtori family; he sent a Facebook message to Agustin Vazquez, an Argentinian military enthusiast, to ask if he knew anything about Daniel or his family. Understandably Agustin’s initial response was very guarded; but Mark then explained that he was aware of the family’s tragedy, and that he wanted to get Daniel’s helmet back to them. An amazed Agustin then told Mark that he did know the family; and that Daniel’s daughter Virginia had with a local policeman, Rolando Hernan Nusz, opened a museum in Chajari to honour Daniel and the other veterans of the conflict.

Mark was determined to get Daniel’s helmet to his family, whatever it might take to do so; but he decided not to contact Virginia straight away, as it was by then the 40th anniversary of the conflict’s end, a very emotive time for veterans and their families. It was not until the 1st July that Mark asked Agustin to contact the Sirtori family to ask if they would be willing to hear from him directly. Virginia replied that they would, and on the 2nd July Mark reached out to her through Facebook with a ‘friend request’, which she accepted.

They have since exchanged many private messages, indeed there has scarcely been a day that they have not been in contact. They have shared their experiences and feelings about the Malvinas/Falklands conflict, and Mark has learnt much more about Daniel and his family. Forty years may have passed since the conflict but Virginia, like Mark, believes it to be very important that veterans, like her father, are remembered with honour; and that displaying the helmet in the museum, with the story of its return, is an appropriate way to do so.

Mark next had to tackle the problem of transporting the helmet safely to Argentina. A bespoke case had already been commissioned for it, but he was concerned that there might be difficulties in sending such an unusual and emotive item by the usual carriers, or taking it as hand luggage on an airplane. Mark contacted potential carriers and official sources for advice and guidance, but there seemed to be no relevant precedents for what he wanted to do. So, he decided to phone the Argentinian Embassy in London to see if they could assist; they were most helpful, indeed the very next day the Ambassador himself, His Excellency Javier Figueroa, asked Mark to contact him. When they spoke, the Ambassador was very appreciative of what Mark was trying to do for the family of an Argentinian veteran, and offered to send the helmet to Argentina through diplomatic channels. The Ambassador also invited Mark and his wife Tricia to have lunch with him, and later he would make direct contact himself with the Sirtori family.

The lunch with the Ambassador took place on the 11th August. Mark and Tricia were deeply impressed by the warmth and courtesy of their welcome. They were shown around the Ambassador’s beautiful London residence by his Personal Assistant, before having lunch with the Ambassador and his Military Attaché, who were very interested to hear all about Mark’s quest. The Ambassador (on the left in the photograph) again expressed his appreciation for what Mark was doing for the Sirtori family; and he clearly had great respect for all those who had fought in the conflict, believing that they should be appropriately recognised and honoured.

In September this year Mark and Tricia will travel to Argentina

to collect the helmet from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Buenos Aires, before travelling north to Chajari to meet Daniel’s family. The local press in Chajari is already publicising their visit, and various events are being organised by veterans and the local authorities. As well as presenting the helmet to Daniels’s family, Mark will also donate some other items to the museum, including a history of the Beauchamp Lodge No.1422, West Kent’s very special military lodge. What would Daniel have made of all this? To know that his old army helmet has travelled so far, and is now helping to bring together veterans and their families.

During his quest, Mark has grown increasingly aware of the similar issues and concerns that affect veterans and bereaved families from both sides of the Falklands conflict, and how the desire to recognise the courage and sacrifices of those who fought can bring them together in mutual support. Indeed, whilst in Buenos Aires Mark will meet with Colonel Carrizo-Salvadores who commanded the Argentinian forces on Mount Longdon. Mark's battalion was fighting against them in June 1982 when his Platoon Sergeant, Ian McKay, won a posthumous Victoria Cross for ‘courage and leadership of the highest order’. Mark and the Colonel fought on opposing sides and have never met, but both saw comrades fall in action, and they have seen at first-hand the ongoing physical and mental cost of such battles.

Finally, it is important that the families should also look to the future, and Daniel’s daughter Virginia will attend the events in Chajari with her baby daughter Renata. Sadly, she will never meet her grandfather; but through her family’s memories, her hometown museum, and meeting with a veteran of the Falklands conflict who travelled half way around the world to bring home her grandfather’s helmet, Renata will grow up knowing to be very proud of Daniel and the other veterans like him.